Find current and past issues on JSTOR, or for more information on the publication or how to subscribe, check out our website.

On the left , the oven in Room IV; on the right, the mud-brick platform after removal of the oven. (Courtesy of the University of Hawaii Tell Timai Project)

BASOR No. 376, Novemberarticle, “A Hellenistic Household Ceramic Assemblage from Tell el-Timai (Thmuis), Egypt: A Contextual View,” by Nicholas Hudson (University of North Carolina).

Large deposits of domestic pottery from primary contexts in Ptolemaic Lower Egypt are uncommon and seldom presented in their entirety. This article presents four primary deposits from the destruction level of a late third/early second-century structure at Tell el-Timai in the Nile Delta (ancient Thmuis). The architectural setting for the deposits is presented, followed by presentations of each deposit in its entirety, organized by functional classifications. Read More …

Site 34 (“Slaves’ Hill”), the largest smelting camp in Timna, looking east. Photo: Erez Ben-Yosef

BASOR No. 376, Novemberarticle, “Back to Solomon’s Era: Results of the First Excavations at “Slaves’ Hill” (Site 34, Timna, Israel),” by Erez Ben-Yosef (Tel Aviv University).

Site 34 (“Slaves’ Hill”) is a large copper smelting camp located on a flat mesa at the center of the Timna Valley. The first excavations at the site focused on the main slag mounds, related metallurgical installations, the gatehouse, and the site’s perimeter wall. The results, coupled with 14 new radiocarbon dates retrieved from short-lived samples, corroborate the recently suggested new chronological framework for Iron Age copper production in the southern Arabah and reveal more information on the nature of copper production at Timna at the turn of the first millennium B.C.E. Read More …

BASOR No. 376, Novemberarticle, “Late Roman Workshops of Beit Nattif Figurines: Petrography, Typology, and StyleArchaeology Returns to Ur: A New Dialog with Old Houses,” by Anat Cohen-Weinberger (Israel Antiquities Authority) and Achim Lichtenberger (Ruhr-Universität Bochum).

BASOR No. 376, Novemberarticle, “Late Roman Workshops of Beit Nattif Figurines: Petrography, Typology, and StyleArchaeology Returns to Ur: A New Dialog with Old Houses,” by Anat Cohen-Weinberger (Israel Antiquities Authority) and Achim Lichtenberger (Ruhr-Universität Bochum).

In 1936, Dimitri Baramki published an assemblage of oil lamps and figurines that he had excavated in two cisterns at Beit Nattif in southern Judaea. This rich assemblage, which was waste material from a workshop, was the starting point to characterize a Beit Nattif style. Read More …

Location of Aila. (Map ©Google Earth)

BASOR No. 376, November article, “A Diachronic Look at the Agricultural Economy at the Red Sea Port of Aila: An Archaeobotanical Case for Hinterland Production in Arid Environments,” by Jennifer H. Ramsay (State University of New York) and S. Thomas Parker (North Carolina State University).

Archaeological investigations carried out by the Roman Aqaba Project seek to reconstruct the economy of the ancient seaport of Aila and contribute new evidence concerning the nature of the imperial Roman economy in the East. This study presents a component of the project that is focused on the analysis of plant remains retrieved from soil samples taken during excavations at Aila.

Photo of a plastered oor below the bench beneath the bema in the Khirbet Shemaʿ synagogue (Meyers and Meyers 1970–1980: box 6). (Courtesy of the Eric M. and Carol L. Meyers Papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University, Durham, NC)

BASOR No. 376, November article, “Debating Ancient Synagogue Dating: The Implications of Deteriorating Data,” by Chad Spigel (Trinity University).

One of the most well-known debates about synagogue dating concerns the synagogues excavated as part of the Meiron Excavation Project. According to the excavators, Eric Meyers, Carol Meyers, James Strange, and Thomas Kraabel, these buildings were constructed in the second and third centuries C.E. Jodi Magness, however, claims that the archaeological evidence supports moving the construction dates into the late-fourth, fifth, and even sixth centuries C.E.

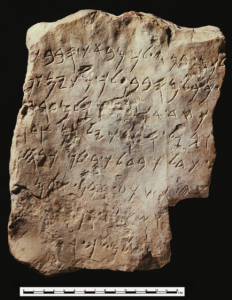

The Amman Citadel Inscription. (Photograph by Bruce and Kenneth Zuckerman, West Semitic Research. Courtesy of the Department of Antiquities, Jordan)

BASOR No. 376, November article, “Line Five of the Amman Citadel Inscription: History of Interpretation and a New Proposal,” by Andrew Burlingame (Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations, The University of Chicago).

The fifth line of the Amman Citadel Inscription has remained an interpretive crux since the publication of the text. While earlier studies recognized its importance for the interpretation of the inscription, the philological difficulties hindering interpretation have generated a growing pessimism with respect to this line, culminating in a recent suggestion that it cannot be translated and may simply be the product of scribal mistakes. In this study, Burlingame offers a new proposal for the interpretation of this line, accompanied by a review of the previous scholarship devoted to its study. To support this proposal, he calls attention to several data that have not been considered in previous studies. Specifically, he argues that {tdlt} at the beginning of the line constitutes a denominative verb meaning “to equip with a door” and point out the overlooked instance of this verb in the Temple Scroll. Second, he offers a new interpretation of {kbh} at the end of the line in light of possible Akkadian and Ugaritic cognates. He aims to illustrate that these proposals allow us to arrive at a more philologically satisfying reading of the line and, in turn, a better understanding of the text as a whole.

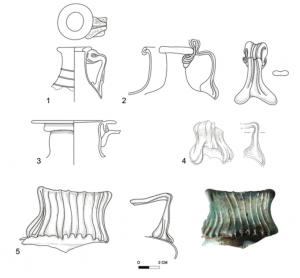

Free-blown jugs from (1) ʿAraq en-Naʿsaneh (Wadi ed-Daliyeh); (2) Cave of Horror; (3) Cave of the Sandal (Cave VIII/28); and (4, 5) ʿAbud Cave. (Drawings by Y. Rudman; photo by P. Shrago; drawings digitally formatted by S. Pirsky; courtesy of the American Schools of Oriental Research, the Israel Exploration Society, the Israel Antiquities Authority, and R. Porat)

BASOR No. 376, November article,“Glass Vessel Use in Time of Conflict: The Evidence from the Bar Kokhba Refuge Caves in Judaea, Israel (135/136 C.E.),” by Ruth Eve Jackson-Tal (Institute of Archaeology, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem).

This article concentrates on the overall analysis of the glass vessel finds, some published here for the first time, recovered in numerous excavations and surveys in refuge caves, in Judaea, Israel. These caves were used by Jewish refugees fleeing the Roman army in the late stages of the Bar Kokhba revolt in 135/136 C.E. The glass vessels consist mostly of daily bowls, beakers, jars, bottles, and jugs. However, a few luxury vessels, such as the renowned molded and wheel-cut bowls from the Cave of Letters, were also found. Therefore, the comprehensive study of the glass finds discovered in refuge caves, used in a time of a major political conflict, offers a rare possibility to promote our understanding of social, cultural, chronological, and regional issues through the study of glass vessel use by a specific ethnic group in a very narrow date frame.

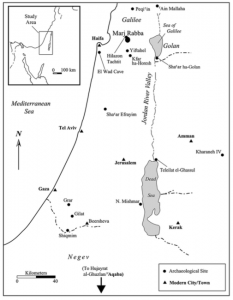

BASOR No. 376, November article, “Gazelles, Liminality, and Chalcolithic Ritual: A Case Study from Marj Rabba, Israel,” by Max D. Price (Peabody Museum, Harvard University), Austin C. Hill (Anthropology Department, University of Connecticut), Yorke M. Rowan (The Oriental Institute of The University of Chicago) and Morag M. Kersel (Department of Anthropology, DePaul University, Chicago).

BASOR No. 376, November article, “Gazelles, Liminality, and Chalcolithic Ritual: A Case Study from Marj Rabba, Israel,” by Max D. Price (Peabody Museum, Harvard University), Austin C. Hill (Anthropology Department, University of Connecticut), Yorke M. Rowan (The Oriental Institute of The University of Chicago) and Morag M. Kersel (Department of Anthropology, DePaul University, Chicago).

Endangered today, gazelles were both economically and symbolically important to the peoples of the ancient Near East. In various contexts, the gazelle has represented liminality, death, and rebirth. Gazelles held special significance in the southern Levant, where archaeologists have documented cases, spanning 20,000 years, of ritual behavior involving gazelle body parts. What roles did gazelles play during the Chalcolithic (ca. 4500–3600 B.C.), a period of both decreased hunting and ritual intensification? In this article, the authors discuss a unique find of burned gazelle feet at the site of Marj Rabba (northern Israel).

Tuttle standing at the southwest corner of the interior, smaller platform, looking north. (Photo by Q. Tweissi)

The BASOR article by TED Prize winner Sarah Parcak and CAORC Executive Director Christopher Tuttle about the discovery that has made headlines is now available to the public! By becoming a Friend of ASOR for free, you’ll get access to the full article on the monumental structure that hid in plain site near Petra.

BASOR No. 376, November article, “Tel Dor and Iron Age IIA Chronology,” by Nadav Naʾaman of Tel Aviv University.

BASOR No. 376, November article, “Tel Dor and Iron Age IIA Chronology,” by Nadav Naʾaman of Tel Aviv University.

The article discusses the date and historical background of the transfer of Tel Dor from Phoenician to Israelite hands. Archaeologically, the transfer was peaceful and took place in the late Iron Age IIA. Na’aman suggests that it happened under the reign of either Omri or Ahab, at a time when Israel expanded on all fronts. Either Tel Dor was endowed as a dowry on the occasion of Jezebel’s marriage to Ahab (cf. 1 Kgs 9:16), or the king of Israel purchased it as part of his alliance with Tyre (cf. 1 Kgs 9:11–14). Dating the Israelite–Tyrian alliance helps establish the date of the transition between the early and late Iron Age IIA.