This post was submitted to the ASOR Blog in response to one of our Ancient Near East Today posts. If you would like to submit a response to a post on our blog, please see our submission guidelines.

By: Gregory L. Doudna

A recent post on the ASOR Blog by C.D. Elledge and Olivia Yeo (“Rethinking the ‘Qumran Community’: Recent Approaches”, December 13) closes with three questions in understanding Qumran identified as likely to shape future studies:

First is determining which texts within the larger Dead Sea Scrolls collection provide evidence for the underlying community. Second, what are the implications of shifting the focus for Qumran origins from the earlier Hasmonean age to a later Hasmonean setting? And third, even among those scholars who associate Qumran with the Dead Sea Scrolls community, how do we determine the precise character of that relationship? Was it a sectarian headquarters, home to a radical offshoot, or one settlement of the yahad?

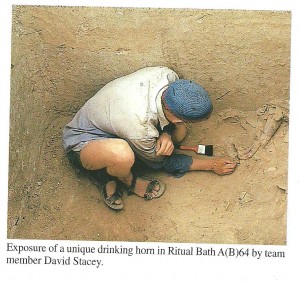

A new analysis of Qumran’s archaeology and texts may shed light on these questions. The archaeological analysis is: David Stacey, “A Reassessment of the Stratigraphy of Qumran”, in D. Stacey and G. Doudna, Qumran Revisited: A Reassessment of the Archaeology of the Site and its Texts (Archaeopress).

David Stacey writes from his experience as an archaeologist who worked for ten years on the Netzer excavations at Hasmonean/Herodian Jericho. Out of this experience Stacey does not interpret Qumran as if Qumran was sui generis, a unique site to be interpreted in light of the contents of the texts found in its caves, its material remains interpreted as reflections of a separatist sect inhabiting the site in an ideological world of its own.

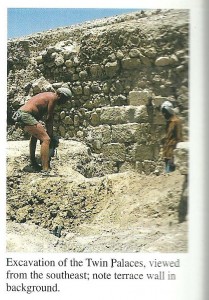

Stacey analyzes Qumran instead from the perspective of regional economic development and industries affecting the site without regard to the contents of the texts. Rather than interpret the remains of Qumran in terms of reconstructed sectarian practices (activities presumed to have included collection and production of the texts themselves), Stacey examines Qumran independently of the texts beyond accounting for the texts’ physical presence. Stacey accounts for the presence of the scrolls in Qumran’s caves in terms of permanent disposals of texts brought to the site for that purpose.

Of particular interest is Stacey’s argument that Qumran was an extension of the Hasmonean estate in Jericho. Although there are precursors to this idea—notably Pessah Bar-Adon’s influential 1981 argument that Qumran was put into operation as part of a Hasmonean program of fortification and exploitation of economic resources near the Dead Sea, such that an interpretation of Qumran as beginning as a Hasmonean state initiative is now embraced by most current studies of Qumran’s archaeology (Humbert 1994, Hirschfeld, Magen and Peleg, Cargill, Mizzi, Taylor)[1]—yet Stacey differs in his analysis in comparison to most others who advocate a Hasmonean state initiative origin of Qumran. For Stacey sees Hasmonean Qumran being further developed by Herod with no fundamental rupture or break in its industries and functioning.

This is in contrast to several of the analyses noted (Humbert, Cargill, Mizzi, Taylor) who suppose there was a radical change in occupation of the site in the time of Herod. In the line of thinking of these analyses, a new group—sectarians—came to Qumran late in the 1st century BCE bringing their scrolls with them and producing more scrolls at the site, which they continued to do until the First Jewish Revolt of 66-70 CE.

The reason these scholars identify a new sect arriving at the site late in the 1st century BCE, and replacing the site’s former inhabitants, is because they wish to account for the presence of the scrolls in the caves associated with the site, and believe this is the way to do so: first a Hasmonean period at the site (no connection to the scrolls), then replaced by the sect connected to the scrolls. This was not Qumran’s excavator of the 1950’s de Vaux’s scheme (de Vaux had the sect at Qumran from the beginning), and abandoned in this scheme is the old idea that a 2nd century BCE Teacher of Righteousness of the texts came to Qumran with his little band of followers to build the site after he was exiled from Jerusalem. But it is a way to keep the traditional model of the sect of the texts and its relationship to the site of Qumran intact, in a modified form.

But why not, a reader who has been following the discussion to this point might ask, simply identify the people of the scrolls as the people operating the site when Qumran was a Hasmonean outpost? Why the necessity to suppose two distinct sets of people?

Such a question seemingly comes from a naive reader unfamiliar with Qumran text scholarship. For if there is one point upon which Qumran text scholars have been in agreement with almost complete unanimity for as long as anyone can remember, it is that the sect of the Qumran texts was opposed to the Hasmonean high priests. In prevailing Qumran scholarship it is considered simply inconceivable that the people of the texts of Qumran could have been favorable to, for example, Hyrcanus II, the high priest of the temple in Jerusalem 76-67 and 63-40 BCE.

In my essay in the same volume (“The Sect of the Qumran Texts and its Leading Role in the Temple in Jerusalem During Much of the First Century BCE: Toward a New Framework for Understanding”), I show that the naive reader’s question referred to above is actually quite astute. My essay challenges the reasons claimed for supposing that the Qumran texts were opposed to the Hasmonean high priests. I show that nothing in the Qumran Community Rule (1QS and 4QS) texts calls for reading those texts as opposed to the temple or to the priests who controlled the temple. I show that such interpretations of the Qumran S texts are unfounded and chimerical, no matter how deeply ingrained such interpretations have been in scholarly discourse.

I show that, in fact, nothing in the Qumran texts calls for supposing the sectarian texts were other than supportive of most Hasmonean high priests. Texts, which have been read as polemical against all Hasmonean rulers and their regimes, instead become polemical against one Hasmonean ruler’s regime, written from the perspective of supporters of a deposed previous high priest in exile. Condemnations in some texts of a Hasmonean regime become not a rejection of all Hasmonean high priests but rather arise out of the authors’ loyalty to, as they interpreted it, the legitimate Hasmonean high priest who had been cast into exile.

Synthesizing work in specific areas of a number of scholars in recent years with analyses of my own into a larger framework I show that traditional arguments for supposing an adversarial relationship between the sect of the Qumran texts and the Hasmonean high priests evaporate upon examination: there is no sign in the texts of calendar conflict between the sect and the Hasmonean high priests; no criticism for combining king and high priest; no notion of rival priestly ancestries; no basis for supposing Davidic messianism in the form in which it appears in the Qumran texts was opposed to Hasmonean high priestly and royal rule; no opposition to Alexander Jannaeus, or to John Hyranus I before him.

Contrary to common conceptions, which have influenced archaeologists’ interpretation of Qumran, none of the notions just named are in the Qumran texts in any way. Instead of the sect of the Qumran texts being opposed to the Hasmonean high priests, the sect of the Qumran texts was the sect of the Hasmonean high priests.

In my essay I interact with work of, among others: Martin Abegg (priests bless the high priest in 1QSb and 1QS); Rachel Bar-Nathan (the pottery of 1st century BCE Qumran is identical to that of the Hasmonean Palace Complex at Jericho); Casey Elledge (Davidic figures in some Qumran texts read as a military commander subordinate to the high priest); Daniel Falk (liturgy and prayer in Qumran texts is likely imitative of temple prayer, not a substitution for temple sacrifices); Yonder Gillihan (the Serekh texts are patterned after Greco-Roman civic associations); David Goodblatt (no necessary conflict between Davidic messianism and priestly monarchism); Martin Goodman (the notion that the Jews of the Qumran texts were separated from the Jerusalem temple is bizarre); Lester Grabbe (“sons of Zadok” never was a high priestly dynasty, is synonymous with “priests”); Susan Haber (temple imagery applied to the community in 1QS does not imply substitution or replacement for the temple); Jutta Jokiranta (“sect” should not be assumed to mean marginal or opposed to the temple); Jonathan Klawans (Sadducees’ belief in free choice as portrayed in classical descriptions is unlikely to have meant a rejection of belief in election, and is echoed in ben Sirach and other wisdom texts among the Qumran texts); Matthias Klinghardt (the Serekh texts parallel Hellenistic associations, reflect temple-supportive synagogues); Israel Knohl (king and high priest are united in the same figure in some Qumran texts); John Reeves (the Essenes of the classical descriptions are mythical, and as conventionally understood as a sociological entity distinct from other Jewish parties, may not have existed); Alison Schofield (the Hasmoneans likely understood themselves to be Zadokites, no reason to suppose otherwise); Sacha Stern (there is no calendar conflict underlying sectarianism in the Qumran texts); Annette Steudel (the Serekh texts precede the Damascus Document, “D” is “rewritten S”); Joan Taylor (Essenes of the classical descriptions are not portrayed as separated from the temple and public life); James VanderKam (no evidence Hyrcanus II was aligned with or influenced by Pharisees); Hanne von Weissenberg (multiple copies of MMT are evidence of continuous acute concern for the purity of the temple cult); and Michael Wise (1st century BCE Teacher of Righteousness).

On the regime in power in Jerusalem alluded to in harshly negative language in the Qumran sectarian texts, I write:

The doomed ruler hung up alive of Pesher Nahum [at 3-4 i 8-ii 1] is Pesher Nahum’s variant on the violent death of the Wicked Priest of Pesher Habakkuk and Pesher PsalmsA. It is the same figure, called by various names and depicted in various ways in these texts. All of this is set in the context of a Kittim invasion, in these texts from the latter half of the 1st century BCE. It is a doomed ruler of Israel portrayed in a context of a Roman invasion, contemporary to the time of these texts’ writing: killed by gentiles … defeated Jewish ruler … Romans … hung up alive … killed by gentiles … second half of the 1st century BCE … Roman invasion … Jewish ruler … Roman invasion … executed … Roman invasion … who could this figure alluded to in these texts possibly be?

In what may come to be regarded as one of the more unusual, indeed astonishing, oversights in the history of Qumran scholarship, so far as is known it seems no previous scholar has proposed that Antigonus Mattathias, the last Hasmonean king of Israel, tortured and executed by the Romans in 37 BCE, might be the figure underlying the Wicked Priest of Pesher Habakkuk or the doomed ruler of Pesher Nahum. The actual allusion of the figure of these texts, Antigonus Mattathias, remained unseen even though it was always in open view, as obvious as it could be. And in wondering how Antigonus Mattathias was missed in the history of scholarship, I include myself, for I too missed this in mystudy of Pesher Nahum.

Antigonus Mattathias came to power in Jerusalem by usurpation in 40 BCE, when with Parthian assistance he forcibly overthrew and drove into exile Hyrcanus II who had been the high priest of the Jewish nation for more than three decades prior to that point. On the identity of the mysterious exiled Teacher of Righteousness of the Qumran texts over whom so much ink has been spilled, my proposed identity again has no prior scholar’s precedent:

The figure the Qumran texts call the Teacher of Righteousness appears to read, very simply and with due allowance for imagination in the world of texts, as an emic or insiders’ portrayal of the figure who was the contemporary high priest during the decades of the most intensive era of composition and scribal copying activity of the Qumran texts. When the priests of the texts, the priests writing the texts, extol their leading priest, this figure is Hyrcanus II. When Hyrcanus II lost his high priestly position through violence at the time of the Parthian invasion, the texts portray the one who overthrew him as the Wicked Priest. The priests of the texts at Qumran were priests for whom Hyrcanus II was their high priest, with all of the deep significance and honor that would have meant in the world of imagination and texts.

This synthesis differs from prevailing scholarly conceptions. I close my essay with these words:

This synthesis differs from prevailing scholarly conceptions. I close my essay with these words:

In conclusion, this is a picture very different from scholarly constructions that have been taken for granted for so long with respect to understanding the sect of the Qumran texts. It is a picture in which the Teacher is not in the distant past to the authors of the Qumran sectarian texts but is instead a living contemporary, or recently deceased contemporary, at the late end of the Qumran texts. … It is a picture that focuses on the 1st century BCE as the center of interest and activity of the sect of the Qumran texts, and it is a picture in which the 1st century CE disappears from the Qumran textual horizon. It is a picture that dismantles the romanticized notion of a parallel history of a Qumran sect, running alongside known history, constructed solely from the texts themselves, invisible to external history. Instead, in this picture the Qumran texts become the literary remains of a sect organized and led by priests associated with the temple during the greater part of the 1st century BCE, texts from the inner world of this sect, texts from inside the 1st century BCE temple, and the invisibility and anonymity of the shadowy parallel sect and its shadowy leader whose name must remain forever unknown of the common scholarly construction vanishes. And finally, as ironic as this may sound, it is a picture in which it may legitimately be said that what scholars have referred to as “the Qumran sect” controlled the temple in Jerusalem during the greater part of the 1st century BCE.

In the past, archaeological analyses of Qumran which follow the method of David Stacey—of interpreting the material remains of the site independently of the contents of the texts—have been marginalized on the grounds that they “ignore the evidence of the scrolls” (which are part of the archaeological realia of the site, it is pointed out). Although my essay stands independently, I place it in the same volume as Stacey’s archaeological analysis for the purpose of shielding from this line of criticism the work of archaeologists who seek to evaluate the material remains of Qumran objectively. I hope my essay will open spaces to allow such archaeologists’ voices to be heard, liberated from the stifling constraints of a long-dominant interpretive filter promulgated in the name of the ancient Essenes.

In fact Stacey’s analysis of Qumran’s archaeology done independently of the texts agrees very well with the texts. Stacey’s argument that Qumran was an extension of Hasmonean Jericho becomes very sensible, given the congruence of ruling priests at Hasmonean Jericho and the disposals of large numbers of religious texts reflective of those priests at nearby Qumran.

It is almost a commonplace among Qumran scholars that Qumran’s original excavator, Fr. Roland de Vaux, was influenced in the formation of his still-influential interpretation of Qumran in quasi-monastic terms because he was a monk. David Stacey sees Qumran quite differently, largely in terms of smelly, dirty, manual and industrial work done at the site only briefly and seasonally through most of its existence. Stacey makes explicit at the end that his interpretation is also influenced by his experience. Stacey’s closing words:

I am not a scrolls scholar, but for many years I worked as a field archaeologist at, inter alia, Hasmonean/Herodian Jericho, Masada, Cypros, and Herodium. Inevitably I do not look at Qumran in isolation, but as just one archaeological site amongst others of the same period and within the same region. In my youth I worked in several countries, either seasonally or as opportunity arose, and my earliest professional involvement in archaeology was little more than a fascinating but pitifully paid alternative to such itinerant work (which sometimes needed subsidising by spells on building sites in Ein Gedi or En Boqeq). Thus I am familiar with seasonal work, have sympathy for those who carry it out, and am acquainted with buildings that were only used seasonally. My intimate knowledge of the regional archaeology tells me that Qumran, for a large part of its active life, could not have supported year-round occupation, and it satisfies my psyche to view Qumran as a predominantly seasonal site, producing, by processes that were unpleasant, articles that were necessary; a place bustling with activity for a few weeks in the year, but, during the harsh heat of summer, lying empty and abandoned to the thirsty, desiccating sun. I am sure the seasonal workforce preferred it that way too.

The volume also includes an analysis of the Qumran cemetery (“Who Were Interred in the Qumran Cemetery? On Ethnic Identities and the Archaeology of Death and Burial”) by Gideon Avni, Head of Excavations and Surveys for the Israel Antiquities Authority. Avni’s analysis is surely one of the most insightful concerning the Qumran cemetery in print. Avni argues tentatively but convincingly that the Qumran cemetery appears to have been a cemetery for nomads of uncertain ethnic and religious identity, not integrally related to the operation of the buildings of the site. Avni writes:

[I]ts similarity to other desert burial sites, its distinctive location close to a junction of desert trails and a permanent water source (the Ein Feshkha springs), and the long duration of its use, indicate a central burial site for the nomadic population living in the region. The shape of the graves and their orientation are not exceptional compared with the other cemeteries, and no conclusion can be drawn from them about the uniqueness of those interred at Qumran … There is no sufficient archaeological evidence to prove the assumption that the Qumran cemetery was used exclusively by a unique population.Footnote

1. P. Bar-Adon, “The Hasmonean Fortresses and the Status of Khirbet Qumran”, ErIsr 15 (1981):349-52 (Heb.), 86 (Eng. summary); J.-B. Humbert, “L’espace sacré à Qumran”, RB 101 (1994):161-214; Y. Hirschfeld, Qumran in Context; Y. Magen and Y. Peleg, The Qumran Excavations 1993-2004. Preliminary Report (IAA); R. Cargill, Qumran Through (Real) Time (Gorgias); D. Mizzi, The Archaeology of Khirbet Qumran (unpub. PhD thesis, Oxford); J. Taylor, The Essenes, the Scrolls, and the Dead Sea (Oxford Univ. Press).

If you liked this article please sign up to receive The Ancient Near East Today via email! It’s our FREE monthly email newsletter. The articles will be delivered straight to your inbox, along with links to news, discoveries, and resources about the Ancient Near East. Just go here to sign up.

~~~

All content provided on this blog is for informational purposes only. The American Schools of Oriental Research (ASOR) makes no representations as to the accuracy or completeness of any information on this blog or found by following any link on this blog. ASOR will not be liable for any errors or omissions in this information. ASOR will not be liable for any losses, injuries, or damages from the display or use of this information. The opinions expressed by Bloggers and those providing comments are theirs alone, and do not reflect the opinions of ASOR or any employee thereof.

Greg, what is wrong with considering Herod as Hasmonean?

Greg, what evidence would you give to say “it may legitimately be said that what scholars have referred to as “the Qumran sect” controlled the temple in Jerusalem during the greater part of the 1st century BCE”? When did “the Qumran sect” lose that control, as you imply it did? “The Qumran sect” controlling the temple means that it was more than a sect, doesn’t it?